By: Benjamin He

Brad Tyrer would tune in on the radio whenever he heard mention of his father.

“I can’t remember how many times I’d be out in the middle of nowhere doing my job driving and there’d be a discussion about NFL Hall of Fame people and they’d mention my dad,” Tyrer said. “It was like, ‘I can’t believe I’m hearing about him in the middle of Iowa,’ and they’re talking about why he’s not in the Hall of Fame, and it was just kind of curious.”

Brad’s father was Jim Tyrer, a standout offensive tackle at Ohio State. He played for the Dallas Texans/Kansas City Chiefs in the AFL. He spent one season with Washington before retiring after the 1974 season. Tyrer was a big part of the team when the Texans/Chiefs won three AFL titles, lost to the Green Bay Packers in the first Super Bowl, and won Super Bowl IV.

At the time, Tyrer, as a member of the all-time AFL team, seemed like an easy fit in the Pro Football Hall of Fame along with 8 teammates. Yet in 1981, the only time his name showed up in the votes, he fell short of the necessary votes required for induction.

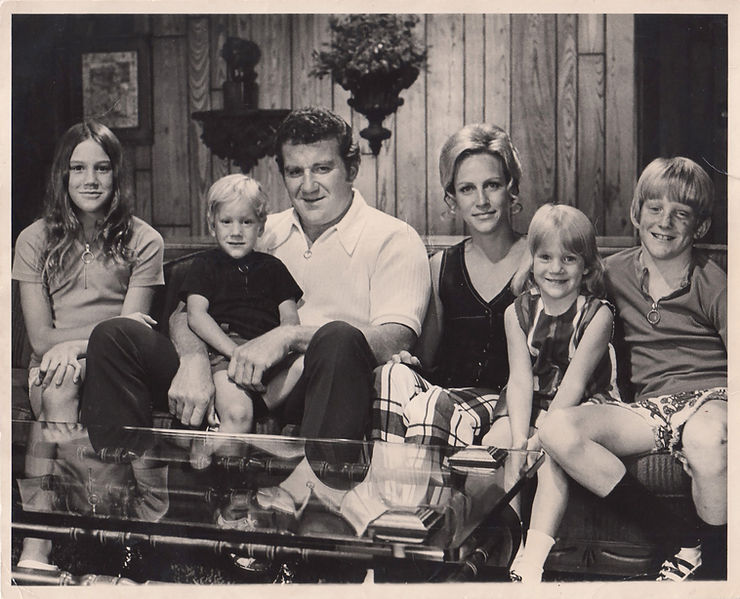

In the morning hours of Sept. 15, 1980, with three of their four children still in the house, 41-year-old Jim Tyrer shot and killed his 40-year-old wife Martha before doing the same to himself.

“We all knew after this happened that something had not been right,” said Jim Tyrer’s youngest daughter, Stefanie. “This wasn’t the man that we knew. . . . You feel like there should have been something you could have done or something you should have recognized. Even though I was 12 or 13, there’s still a little bit of guilt. Why didn’t we pick up on something, or why didn’t we know more? . . . He probably didn’t understand what was happening to him, either.”

Even if Jim Tyrer never shows up in the Hall of Fame, his legacy is secured by his offspring.

To remind people of their parents, the Tyrer children retold their memories about their parents in a documentary by Kevin Patrick Allen. That night, they had hidden when they heard the shots until finally came out to see the horrific mess.

They remembered Martha as a wonderful mother who attended all of their games, and Jim doing so when he had enough time. Jim unfortunately found himself in a financial spiral later on. At the time of his retirement, athletes often needed to take up off-season jobs to feed their families.

“I was a 17-year-old,” recalled Brad, the elder of the Tyrers’ two boys and a high school football player. “I was into myself. I knew my dad went to work and came home at night, but I didn’t really know exactly what he was doing. The night that it happened, I was in my room lifting weights pretty hard because I was trying to get bigger — I was actually measuring my biceps.”

“My dad came in, probably around 9, and he basically had the conversation you have with your oldest son,” he continued. “He had the conversation with me like he knew he was never going to see me again. At the time, it was just so out of context and I was kind of focused on something else. Looking back, I remember that conversation really well. He was saying: ‘You’ve been a good son, and I’m proud of you. You need to take care of your brothers and sisters.’ It was just out of the blue. I was like, ‘Okay, Dad.’ That was probably about a 20-minute talk, but I know he already knew that he was going to do something.”

Jim’s last afternoon was spent with his smallest son, 11-year-old Jason, at a Chief’s game. Jason had said that his father wasn’t overly affectionate up to that point. “He didn’t hug us a lot, but that game he did. I got this kind of — it felt unusual, you know?”

Jim Tyrer wasn’t the smallest of men, either. His full height was 6-foot-6, and he weighed around 300 pounds. He was quite famous for having a head that was a lot bigger than the average human’s. That earned him the nickname “The Pumpkin.” Teammates would joke that “his wife would lend out his head on Halloween.” Ben Davidson, the Raider’s defensive end, had once joked that Tyrer “basically wore a big red trash can as a helmet.”

Stefanie, a pediatric surgical nurse at a Kansas City hospital, was a week shy of her 13th birthday when the shootings occurred. She remembers her father’s huge, special helmet from Ohio state that had his name branded on it because no others could fit him. Jim’s head was a weapon he wielded openly and fearlessly on the field.

Tina Tyrer Moore, the eldest of the four children who was in college at the time of her parents’ deaths, owns one of Jim’s helmets. She stated that the padding isn’t even a half-inch thick.

Brad said that he didn’t remember any specific conversations with his dad about concussions, but he remembered quite a bit of talk about head pain. “Because they couldn’t get an outer helmet shell large enough, I somewhat remember that they would remove material from the inside (padding and suspension) to allow for more room inside.” Brad wrote.

After the shootings, Martha’s parents Truman and Lucille Cline came to take care of the children. Truman was a great example of how to overcome loss for the children. He had experienced tragic loss as well, for he had lost both legs and an arm in an auto accident when he was younger. He had gone on to become an inventor who was appointed by President Ronald Reagan to the Architectural and Transportation Barriers Compliance Board.

Brad, now a 59-year-old businessman and father of two sons, now lives in Louisville. He focused on football for a while. Just days after the deaths of his parents, Brad was back on the field at Rockhurst High, a Jesuit all-boys school that is traditionally a Missouri football power. There, Brad had felt where he truly belonged.

“After the funerals, everybody came over to our house and it was just packed,” Brad said. “Everyone was there — [Chiefs owner] Lamar Hunt and his wife, tons of players and their wives, all kinds of people just packed into this house. To get away from everybody, I went outside and sat down on the concrete patio slab. I put my head down and was kind of whimpering when God came up to me and it was like: ‘Snap to it. Why are you sad? You had two great parents for 17 years. You know nothing. You’ve got nothing to be sad about.’ And it was like a lightbulb went on. I was at peace right then and there with it.”

Even though his children were sad about his death, they had to be realistic about everything else, and that includes his chances of getting into the Hall of Fame.

“None of us really had been upset or frustrated,” Brad said. “I would think about it but only every now and then. . . . We as a group have talked about it and naively thought: ‘Maybe? Who knows?’”

Stephanie has decided not to have children, unlike some of her other siblings, choosing instead to help them.

“I have a lot of context to compare myself with in a sense that I see some kids who are in such difficult situations,” Stephanie said. “I know that my story is nothing compared to the lives that they are living or the challenges that are ahead of them. That gives me a lot of perspective — it shaped how I view the world.”

Source: https://drive.google.com/drive/u/0/folders/12huDbOyPsf5h891AHZBb4U8xSPjorRt2