By: Karen Zhu

It’s July 1945, and J. Robert Oppenheimer and the other researchers part of the Manhattan Project are preparing to test the long-awaited atomic bomb in a desert in New Mexico. However, they barely knew what damage such a mega-weapon would cause.

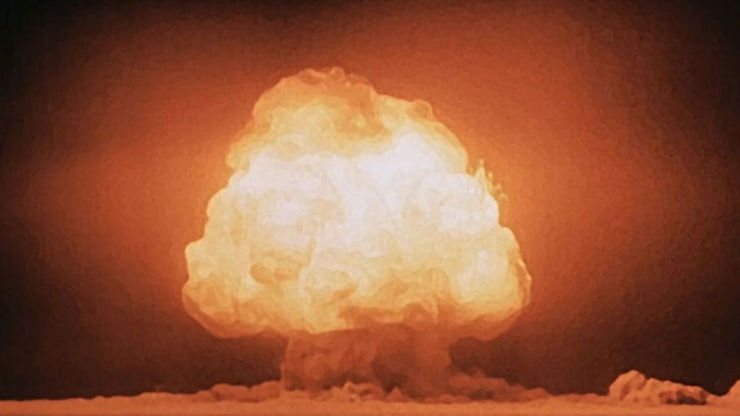

Trinity

On July 16, the device was set on a 100-foot-tall metal tower in a test codenamed “Trinity.” The resultant blast was much stronger than expected. The irradiated mushroom cloud also went many times higher into the atmosphere than expected—some 50,000 to 70,000 feet. Where it would ultimately go was anyone’s guess.

New Study, Old Facts

A new study was released on Thursday, showing that the mushroom cloud and nuclear fallout went farther than anyone had expected. The study’s authors say that radioactive fallout from the Trinity test reached 46 states, Canada, and Mexico within 10 days of detonation. “It’s a huge finding and, at the same time, it shouldn’t surprise anyone,” said the study’s lead author, Sébastien Philippe, a researcher and scientist at Princeton University’s Program on Science and Global Security.

The study also reanalyzed the radioactive fallout from 93 aboveground U.S. atomic tests in Nevada, creating a map of the deposition of radioactive material in the U.S. The drift of the Trinity cloud was monitored by Manhattan Project physicists and doctors, but they underestimated its reach. “They were aware that there were radioactive hazards, but they were thinking about acute risk in the areas around the immediate detonation site,” said Alex Wellerstein, a nuclear historian at the Stevens Institute of Technology in New Jersey. They had little understanding, he said, of how the radioactive materials could embed in ecosystems, near and far. “They were not really thinking about the effects of low doses on large populations, which is exactly what the fallout problem is.”

Unaware

“One of the most striking revelations from the study is that many New Mexicans living near the Trinity test site were left out of the initial RECA legislation, despite being heavily impacted by the fallout. Senator Ben Ray Luján, a New Mexico Democrat, expressed his concern and raised questions about this omission, leaving many wondering why these civilians were not adequately considered in the compensation process. Census data from 1940 shows that as many as 500,000 people were living in a 12-mile radius of the test site. Some families lived as close as 12 miles away, according to the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium. Yet the civilians were not warned about the test ahead of time and weren’t evacuated before or after the test.

The study also revealed significant deposition of radioactive materials in several states, including Nevada, Utah, Wyoming, Colorado, Arizona, and Idaho. Furthermore, numerous federally recognized tribal lands were affected, potentially reinforcing the claims of those seeking expanded compensation in these regions. Although Dr. Wellerstein said that he approaches such reanalysis of historical fallout with a certain amount of uncertainty, mostly because of how old the data is, he also said there is value in such studies by keeping nuclear history and its legacy in the public discourse. “The extent to which America nuked itself is still not completely appreciated still, to this day, by most Americans, especially younger Americans,” he said.