By: Chris Cheng

Otodus Megalodons, one of the biggest meat-eating sea creatures, were warm-blooded creatures; this unique quality turned out to be thecause of both their reign and fall.

The scientists studying Megadalon fossils shared their findings June 26 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. After chemical measurements, scientists drew conclusions that the shark had higher temperatures inside the body than did the surrounding waters. Data of the carbon and oxygen show that the shark’s average temperature was 27 Celsius, which is seven Celsius higher than the average water temperature at the time of their existence.

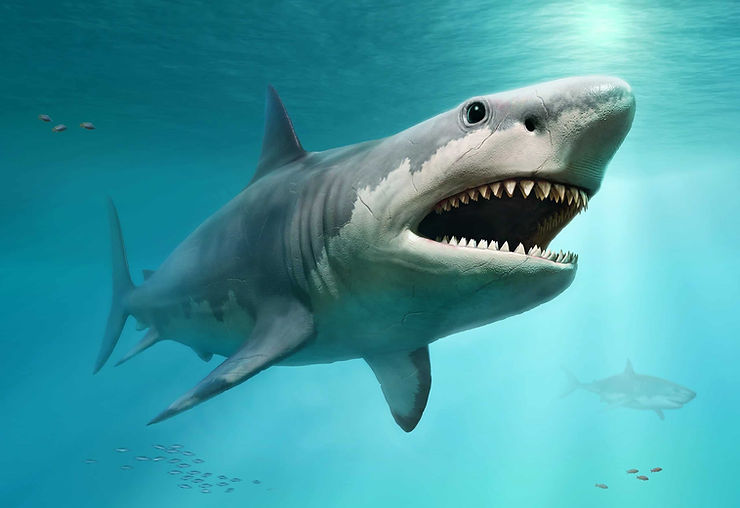

Megalodon sharks are gigantic sharks that can grow up to even seventy feet. Clearly, this tells us that they needed a voracious appetite and source of food to keep on living. However, the appetite could’ve also caused its downfall.

An animal’s metabolism is when its cells set a chemical reaction that changes food into energy. Massive bodies like the Megalodon’s must’ve needed vast amounts food to cycle their metabolisms. “Massive sharks may have been particularly vulnerable to extinction when food was scarce,” a Marine Biogeochemist, Robert Eagle says, one of the scientists on the team that tested the Megalodon’s teeth.

Many mammals can still power their metabolisms in colder environments through warm-bloodedness. Some fish, both extinct or still living, have regional war-bloodedness, which maintains only some body parts to have higher temperatures than the waters. Many modern sharks like the Great White also have this ability.

The Megalodon hunted in cool and warm temperatures, which means they could have maintained even temperatures in their bodies. However, the Megalodon went extinct around 3.5 to 2.6 million years ago, just in time for the arrival of the Great Whites around 3.5 million years ago. Being much smaller than the Megalodon the Great White probably way less food to cycle up their metabolisms.