By: Richard Zhao

In 2018, scientists from the Institute of Physicochemical and Biological Problems in Soil Science Ras in Russia thawed out two worms that were buried approximately 130 feet in permafrost. After thawing, the worms were still alive and managed to produce several more generations of worms in the lab.

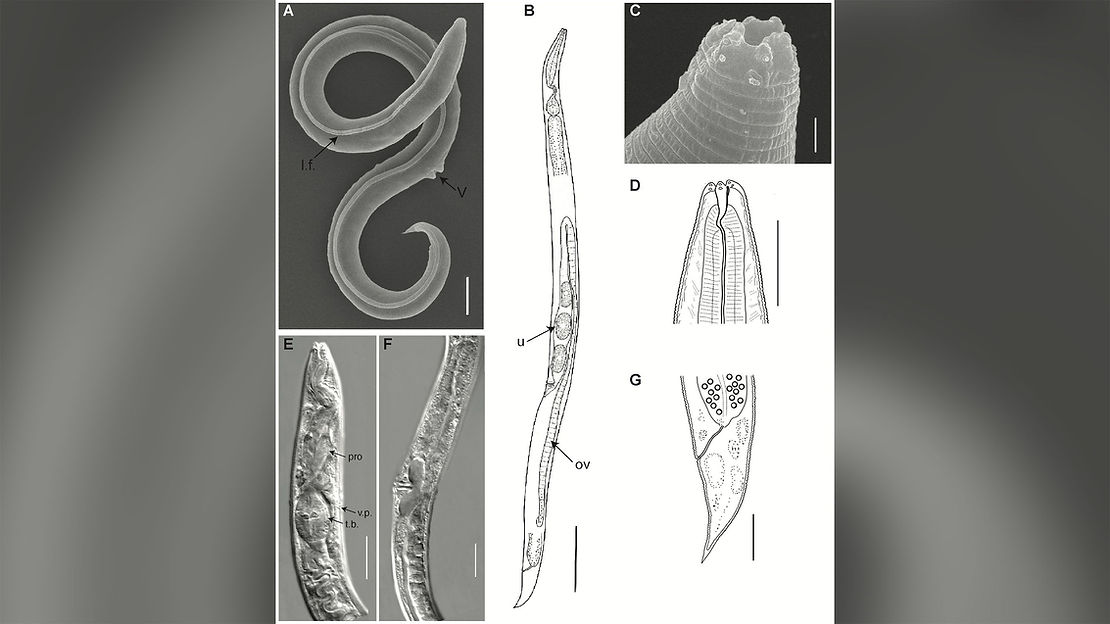

By using radiocarbon dating scientists determined that the worms, called Panagrolaimus kolymaensis, were likely frozen between 45,839 and 47,769 years ago. By entering a dormant state called cryptobiosis, the worms can survive extremely low temperatures. Scientists are currently trying to understand the process of cryptobiosis, as it could lead to practical uses for humans in the future. “The major take-home message or summary of this discovery is that it is, in principle, possible to stop life for more or less an indefinite time and then restart it,” Dr. Kurzchalia, a professor working with the worms, said.

Upon thawing, the worms produced several generations before eventually perishing. This was not unexpected by Dr. Kurzchalia, as other nematodes have been known to be able to reproduce after thawing. However, this was still a joyous occasion for the researchers, as they now have over 1,000 descendants of the original two thawed worms to research.

Researchers have already identified genes in the worm that allow it to achieve cryptobiosis. Dr. Kurzchalia states that while there are no clear practical applications for cryptobiosis yet, the lack of current uses should not be a reason to stop researching the worms. He hopes that one day, cryptobiosis could be used by humans. The discovery of semiconductors, or of the double helix structure of DNA, he said, took decades to yield a practical use, but ultimately turned out to be revolutionary. Likewise, discoveries related to how the worms pause their life could prove to be useful in the future.

Despite the discoveries found by unearthing ancient microorganisms, some are worried that doing so could be harmful to humans. Dr. Kurzchalia admits that it is theoretically possible for thawed organisms to be a threat to the general population, as they could potentially infect humans and cause a pandemic. However, he emphasizes that all tests are conducted in lab-controlled settings, which mean that the possibility of an outbreak happening is extremely low. What Dr. Kurzchalia is worried about is the threat of global warming thawing permafrost, which could introduce uncontrolled organisms into the world. If those organisms are released or are nolonger contained in a lab environment, one of them could find a way to infect humans and cause a pandemic.