By: Sarah Wang

After living over half his life with HIV, a 66-year-old patient at the cancer and research center City of Hope was cured of HIV last Wednesday. He received a transplant of blood stem cells with a rare mutation, one which scientists are trying to replicate.

Although the mutation seems like a cure-all solution for HIV, it’s uncommon and not nearly enough to treat the 38 million people currently living with HIV, as the stem cell is only found in 1 in every 100 Europeans. Even once the mutated stem cell is acquired, the surgery itself is a risky process. So far, patients in dire conditions have been the only ones to receive this transplant.

The road to curing HIV has always been long and demanding, beginning with the federal approval of the drug AZT in 1987, which used protease inhibitors to reduce the virus in the body. The allowance of a drug called PrEP in 2012 was one step further down the road, with the drug inhibiting healthy people from getting the virus.

Because of these developments, the life expectancy of a person with HIV significantly increased from 1987 to now. A patient getting infected in their 20s is expected to live another 54 years on average, according to a 2017 study.

The City of Hope patient received the transplant from a donor in 2019 and has been on antiretroviral medicine since. After the patient was diagnosed with acute leukemia, the doctors at the City of Hope agreed to give him the surgery he needed.

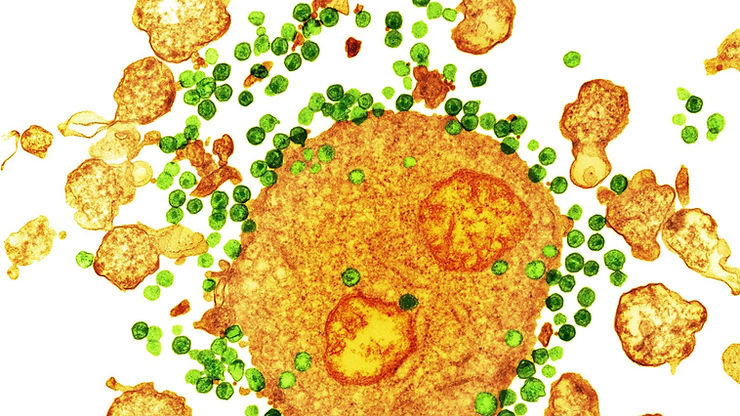

The blood stem cell mutation, CCR5-delta 32, prevents HIV from entering the immune system through a cell receptor known as CCR5. HIV uses CCR5 to enter the victim’s white blood cells, which help with the body’s disease defense. HIV kills the white blood cells, leaving the immune system weak and unprotected from viruses and bacteria.

“This is one step in the long road to cure,” said William Haseltine, a former Harvard Medical School professor who founded the university’s cancer and HIV/AIDS research departments.

However, the anonymous City of Hope patient wasn’t the first to receive this treatment. In 2007, Timothy Ray Brown was cured of HIV by a medical team in Berlin who used the same mutation. After the procedure, there was no longer detectable HIV in his blood.

“The message to people living with HIV is that this is a signal of hope,” said Eileen Scully, associate professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.“It is feasible. It has been replicated again. It’s also a signal that the scientific community is really engaged with trying to solve this puzzle.”