By: Crystal Ge

Itis 1917 and in Russia the Bolsheviks have seized

power, de-throning the Tsar and declaring a revolutionary

communist regime that would transfer the means of

production to the people. Within a year, the royal family and

their entourage lie dead as imperialism is violently dismantled

to make way for Russia’s radical new future.

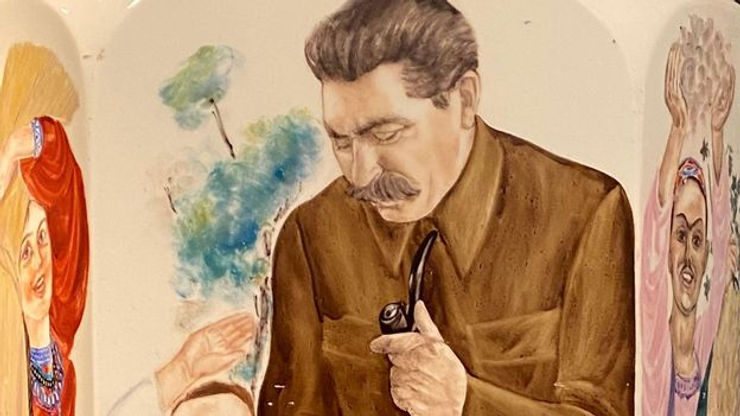

But one important remnant of the old order remains: the

Imperial Porcelain Manufactory (IPM) on the outskirts of the

city now known as St Petersburg. More like this: – How a

painting fought Fascism – Can propaganda be great art? – Why

Orwell’s 1984 could be about now Renaming it the State

Porcelain Manufactory, the Bolsheviks, under Vladimir Lenin,

took control of this symbol of tsarist decadence, seeing

surprising potential in it as a wheelhouse for artistic

innovation and the production of propaganda. Stocks of

unpainted, snow-white china became a tantalising canvas for

avant-garde artists keen to express their utopian ideologies

and rouse enthusiasm for the new socialist era, giving this

delicate, bourgeois material an unexpected, almost

contradictory, second life. In a curious twist, crockery once

intended for the lavish feasts of the Romanovs was now

emblazoned with militant Reds trampling upon their white

ermine furs (Adamovich, 1923). Danko’s porcelain chess set

(1923) used the same colour play, with a red army taking on a

white skeleton king whose proletariat pawns are in chains.

Forced famine, mass incarceration and summary executions

had left the utopian vision of 1917 in tatters. There are many

things one can buy at an auction, especially if you’re looking

for a good antique. Dining chairs, for example. Maybe a nice

set of curtains. When the barrister Cecil Chubb attended an

auction in Salisbury, Wiltshire in 1915, his sights were set on

something domestic. But in that feverish atmosphere of the

auction house – a place where it’s easy to get swept up in the

thrill of bidding and fear of losing out on something one of a

kind – he made an unexpected purchase. He bought

Stonehenge for £6,600 (about £680,000 by today’s value). It

happened, he said, “on a whim”. Chubb, who was the last

private owner of Stonehenge, only laid claim to the site for

three years. In 1918 he passed the stones into public

ownership, where they have remained ever since under the

care of English Heritage.