By: Isaac Yuan

46,000 years ago, when the wooly mammoth ruled the Earth, two worms were buried deep under permafrost. Then, millenia later, they woke up in a laboratory and began to wiggle again.

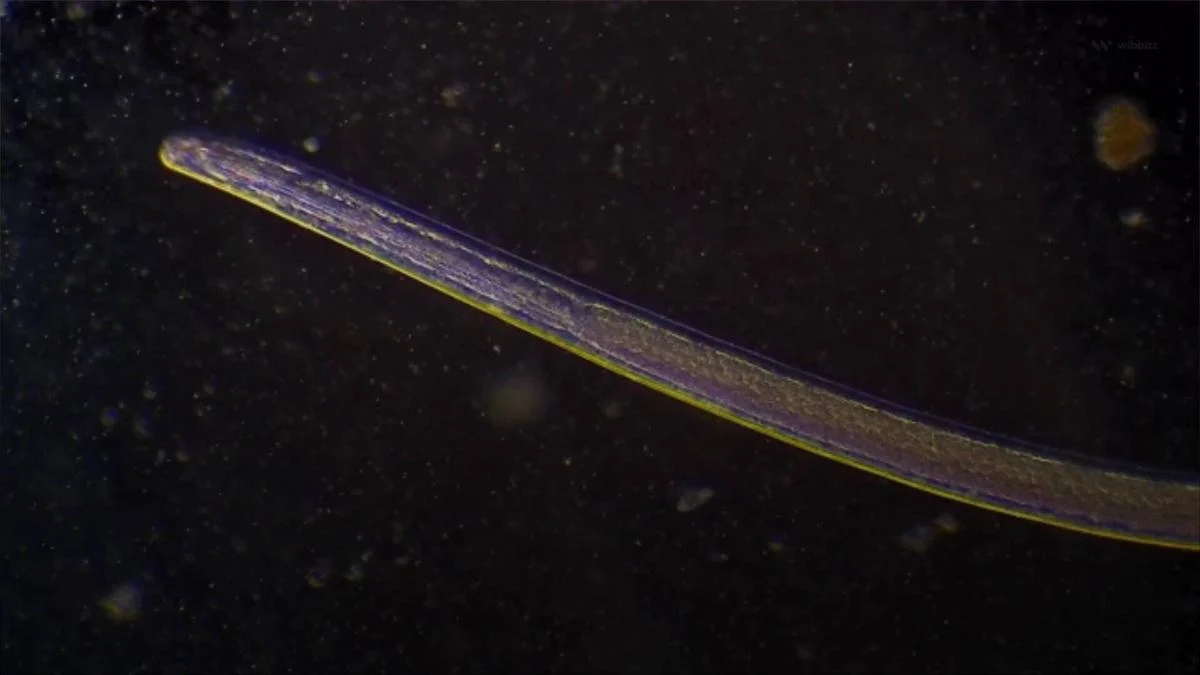

This discovery gives us an understanding of how the worms, also called nematodes, can survive in extreme conditions for astounding periods of time—in this case, tens of thousands of years.

In 2018, Anastasia Shatilovich, a scientist in Russia who studies at the Institute of Physicochemical and Biological Problems in Soil Science RAS, thawed two female worms from a fossilized burrow dug by gophers in the Arctic.

Then, when they found the worms encased in the permafrost, all they had to do to revive them was put them in water, researchers said. Using radiocarbon dating, they determined the millimeter-long worms were frozen between 45,839 and 47,769 years ago, during the late Pleistocene.

These worms were able to survive in extremely cold temperatures by entering a dormant state called cryptobiosis, a process researchers at the institute have been trying to understand. Teymuras Kurzchalia, a professor at the institute who was involved in the study, said that no nematodes had been known to achieve such a dormant state for thousands of years.

Researchers identified key genes in the nematode that allow it to achieve cryptobiosis. They found out that the same genes were found in a fellow nematode named Caenorhabditis elegans, which can also execute the cryptobiotic state.

“This led us, for instance, to understand that they cannot survive without a specific sugar called trehalose,” Dr. Kurzchalia said. “Without this sugar, they just die.” However, the worms still died because nematodes’ life spans are measured in days.

Another researcher in the study, Dr. Philipp Schiffer of the Institute for Zoology at the University of Cologne, said the more suitable application of the findings is that in times of global warming, we can learn a lot about adaptation and extreme environmental conditions from these organisms, illuminating conservation strategies and protecting ecosystems from collapsing.

Though the ancient worms in the study died, that outcome was not unexpected given their life cycle, Dr. Kurzchalia explained.

The worms were sleeping beauties, but when they woke up, they didn’t live for another 300 years.